Wildfires are disturbing the soil microbiome, leading to less tree regrowth and ecosystem change

Plus, how to fireproof your home, AI fire detection, and one college’s wildfire plan

We are Michaela Ocko, Polina Panasenko, and Lorelei Smillie, here to kick off the newsletter.

Scientists at Colorado State University published research about the effects of wildfires on the soil in Colorado forests, revealing that it takes 60 years for organisms and microbes in the soil to reach pre-burn levels.

Last month, Colorado College students spoke with scientists at CSU Fort Collins who study microbial organisms and their interactions with environmental processes.

As wildfires increase in frequency and severity in Colorado, research to support regrowth planning is becoming more essential in wildfire preparedness.

Mike Wilkins, a professor in the department of soil and crop sciences at CSU, gave a presentation on March 31 to Colorado College students about the effects of wildfires on the makeup of the soil. Wilkins brought in two students to present their original research about what the contents of the soil microbiome look like after a fire.

The research, titled “Soil microbiome feedbacks during disturbance-driven forest ecosystem conversion,” was originally published in the International Society for Microbial Ecology Journal in 2024. Authored by 12 scientists, including Wilkins, the paper describes the effects of pile burning, a forest management practice, on soil microbial communities and plant growth in the subalpine conifer forests of the Southern Rocky Mountains.

What is the soil microbiome? The term refers to the diverse community of microorganisms, such as bacteria, microbes, and fungi living in the soil. These tiny organisms contribute to the health of the entire ecosystem since they increase nutrient levels in the soil, promote root growth, and support plant growth. Without these microorganisms, plants would be unable to gain the necessary nutrients to survive.

External factors like heat can drastically alter the soil microbiome, especially when fire is applied to the surface of the soil. In order to examine the effects of wildfire on the soil, the scientists found samples from a variety of different burn sites and examined the changes in the soil microbiota.

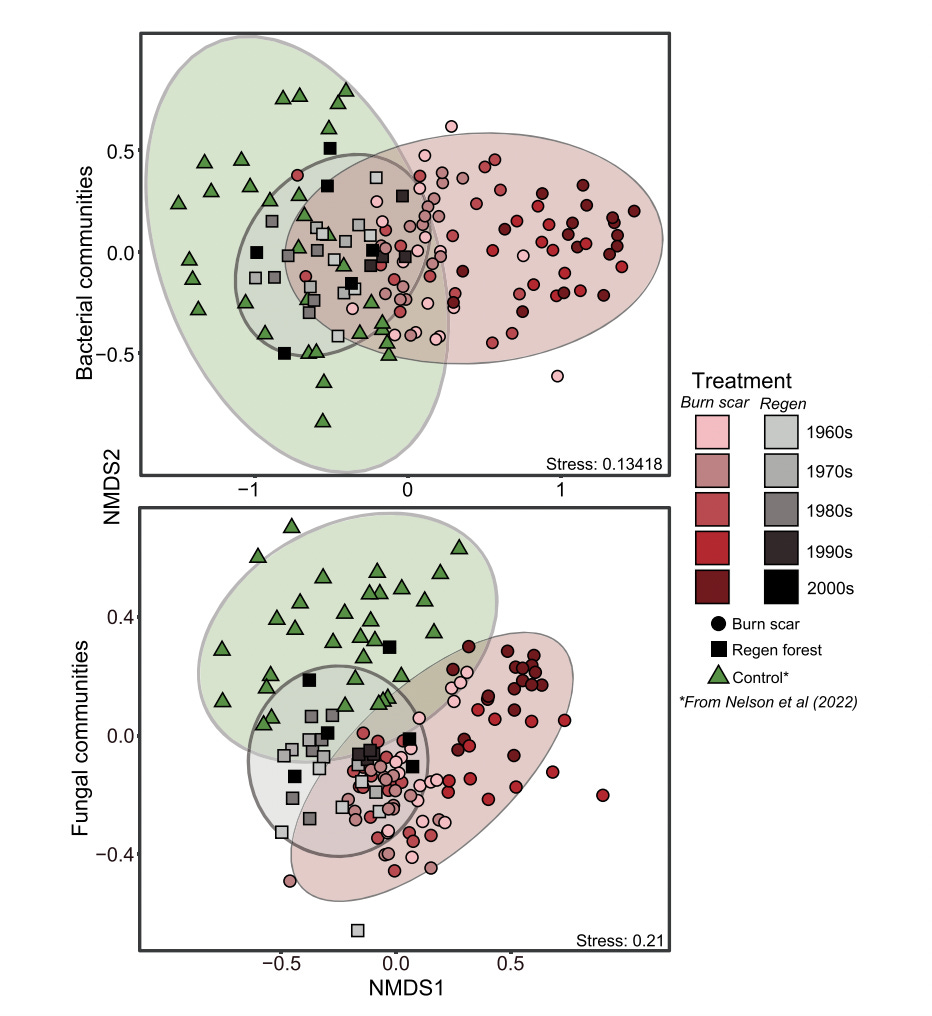

Researchers took samples from five different pile burn sites, located in Northern Colorado Lodgepole pine forests, that burned over a range of decades, including the 1960s, 1970s, 1980s, 1990s, and 2000s. They then studied the soil to measure the changes in vegetation diversity after the burn compared to the soil samples from the areas nearby that didn’t burn.

Pile burning refers to burning leftover wood from logging to prevent wildfires. It’s a wildfire mitigation technique that aims to reduce the amount of dry brush and fallen trees that could contribute to a larger wildfire. The intense heat from pile burning acts as a proxy wildfire for scientific study, and examining the aftereffects can provide answers to what happens in an environment post-wildfire.

The researchers found that burn scars have lasting impacts on the key functions of the soil microbiome.

Samples collected from burnt areas showed significantly less gene diversity and demonstrated decreased capability of creating cobalamin – the enzyme contributing to the plant recovery in the burn scars.

The graph above illustrates the comparison between the burnt and unburnt samples of bacterial and fungal communities. The green ovals show samples from the control group that remained unburnt, next to the red ovals that include samples from the burn scars. Grey ovals mark the samples from regenerated forest that once burned but have shown signs of regeneration.

Wilkins and his team concluded that after a burn, the soil microbiome took 60 years to recover to healthy levels. That can have a variety of effects on vegetation in a given area, including permanent ecosystem changes from forest to grassland or a lack of vegetation growth entirely.

These changes risk creating an ecosystem that is less resistant to fire or drought, causing a feedback loop that could eventually bring more fire into the forests.

Climate change, weather patterns, and other human-caused phenomena will increase fire severities and frequencies, decreasing soil diversity and changing the soil microbiome and wider ecosystem.

Wilkins called increasing wildfire “one of these global change disturbances” that impacts the microbiome and “the functions that it performs.”

“These disturbances can cause a loss of fungi, some of which have symbiotic relationships with the trees,” he said. “With the lack of fungi, the trees are less likely to regrow.”

Studies by scientists like Wilkins and his students contribute to a growing body of research about the human role in wildfire mitigation and recovery efforts.

“If these forests disappear through megafires,” Wilkins said during his presentation, “there’s going to have to be a whole change in our way of living in the western U.S.”

How to fireproof your home

I’m Lorelei Smillie, a political science and journalism student interested in solutions-oriented journalism.

Raging Colorado wildfires are threatening homes, but some solutions are on the horizon.

As wildfires increase in number and severity in Colorado, homeowners must take preventative measures to ensure the safety of their property. Often easier said than done, wildfire protection strategies can be costly and complicated. However, there are tangible strategies homeowners can take to reduce the risk of their home burning down.

“No home is entirely fireproof, especially under extreme conditions, but it is absolutely feasible to build a fire-resistant structure,” wrote Caleb Ashby, the public affairs specialist for the National Interagency Fire Center, in an email.

According to Ashby, the No. 1 cause of homes burning down is an ember floating onto the structure and igniting it. Embers can travel from miles away and ignite homes by entering attic vents, collecting in roof gutters, or catching in corners where debris has accumulated.

Combustible vegetation nearby the house can also play a large role in increasing risk. Ornamental shrubs, unmanaged grasses, and low-hanging tree limbs can lead a fire directly onto your home. In addition to this, flammable building materials used to construct the home can pose a large problem.

A structure does not need to be directly in the fire’s path to be at risk.

Low-cost steps to take:

Establish and maintain defensible space by removing flammable vegetation within at least 30 feet of a structure

Retrofitting the home with noncombustible roofing, siding, and decking materials

Store flammable materials away from the home, not under decks or next to walls

“Maintenance is key,” wrote Ashby. “In my experience, consistent maintenance combined with sound building practices makes the most meaningful difference in structure survivability during a wildfire event.”

Although individual homes might be built to be fireproof, unmaintained houses surrounding yours can also pose a risk. Unified action is essential, since a well-prepared home surrounded by unmanaged properties is still in harm’s way.

The cost of retrofitting a home varies widely based on location and project scale. Estimates range from a few thousand dollars to $20,000 or more.

“New construction designed with fire resilience in mind may cost 10 to 20 percent more than conventional building,” wrote Ashby. “But those upfront investments can lead to savings in insurance premiums and, more importantly, significantly improve survivability.”

Early wildfire detection is critical. These companies are using AI to alert authorities before a human response.

I’m Anders Pohlmann, a senior geology major interested in the latest technological advancements in the battle against climate change.

When it comes to wildfires, timing is everything. The early minutes and initial response time from authorities can make a critical difference for human lives and property.

In recent years, researchers and firefighting agencies have deployed artificial intelligence as the latest technique to shorten these critical time periods.

Agencies have used AI to differentiate smoke from dust, clouds, and foliage. Additionally, AI-powered cameras can pinpoint the exact location of a fire’s origin, allowing first responders to easily receive directions.

While many wildfire mitigation startups have been founded recently, one organization has been using high-resolution motion detection cameras to scope out wildfires and other natural hazards for more than 20 years.

Based out of the University of California in San Diego, ALERT California and its private partners have become one of the leading programs installing sensors in the state most prone to wildfires. As AI led to new technologies in 2023, ALERT California partnered with CALFire and Digital Path to create and install new AI-powered sensors in wildfire-prone areas.

Traditionally, humans have reported wildfires first. This has led to longer response times in remote locations, as well as longer response time for fires that spark up in the middle of the night. AI-driven sensors, however, can directly alert authorities without a human witness being necessary.

Last year, a small vegetation fire near Irvine Lake in Southern California marked the first time Orange County authorities learned about a fire without an emergency call. An ALERT California sensor notified the Orange County Fire Authority of an “anomaly” at 2 a.m., and notified the Orange County Fire Authority who quickly extinguished the blaze.

During the Los Angeles wildfires of 2025, ALERT California’s sensors detected fires early.

“ALERTCalifornia’s cameras were used to identify fires in the incipient phase and support emergency managers in monitoring the fires and enhancing situational awareness through the incidents to containment,” a spokesperson for ALERT California said. “ALERTCalifornia’s cameras are available to all, so the public was empowered to use the camera data to enhance their own decision making during the emergencies.”

In Colorado, another startup has already made an impact by partnering with utility companies, ski resorts, and government agencies, among others.

Pano AI, a San Francisco-based startup, has created a system called Pano Rapid Detect, which uses deep learning AI to identify wildfires. Colorado utility companies such as Xcel Energy, which faced more than 300 lawsuits after a downed powerline, was cited as one of the sources of the Marshall Fire, have turned to Pano AI for future wildfire mitigation.

Colorado Springs Utilities is currently considering using the company as part of its wildfire plan.

Pano AI has a patented triangulation system that determines the precise coordinates of a wildfire’s origin. The triangulation system is possible due to multiple cameras present in the same area, each spanning a 10-mile radius.

When the June 2024 Douglas County Bear Creek Wildfire broke out, Pano AI provided triangulated coordinates and video footage which led to full containment at three acres within a day.

A spokesperson from Pano AI wrote in an email that stakeholders displayed a significant increase in interest following the January 2025 Los Angeles wildfires, particularly in populated areas on the wildland-urban interface. “Our approach hasn’t changed-but what has changed is the level of awareness.”

This progress in early wildfire detection does not come without a cost. The typical pricing for a Pano AI station is $50,000 per year. The cost covers a full subscription-based service, combining ultra high definition cameras, daytime and nighttime detection, satellite feeds, weather data, and a 24/7 staffed intelligence center.

A proposed new law, SB25-011, in Colorado seeks to address this issue, with more than $6 million allocated to installing new camera stations such as the ones provided to Pano AI.

The bipartisan legislation would pay for the bill using money from the state-owned real property fund from the sale of state property. That fund is unused at this moment, and is the most likely source of funding as policymakers look to potentially slash the state’s general fund by more than $1 billion.

What is Colorado College’s Wildfire Plan?

I’m Michaela Ocko, an environmental studies major and journalism minor, here to explore the extent to which Colorado College has a wildfire mitigation plan.

On June 23, 2012, the Waldo Canyon burned more than 13,000 acres of land approximately four miles from Colorado College.

It was the first of two notable fires in Colorado Springs, and the city has continued to see smaller ones since then.

Fire seasons have increased in longevity from the traditional season of May to September, and now burn well into the winter. Colorado College isn’t in the Wildland Urban Interface, or WUI, a zone that is monitored for wildfire danger.

“The college is not in a high-risk area,” said Ashley Whitworth, the wildfire mitigation program administrator for the Colorado Springs Fire Department.

She works with residents typically located to the West of I-25, in the WUI zone, and said she is unaware of any plan that the college might implement to prepare for or combat wildfires.

There is, however, a team on campus that is responsible if an emergency were to impact the campus.

Ryan Hammes, the assistant vice president for administrative services at Colorado College, said CC has an incident management team that handles “crisis management” for the institution.

Hammes is also a volunteer firefighter.

In addition to an Incident Management Plan, there is also an Emergency Management Plan, which mentions wildfire response once in its 18 pages.

“Readiness actions may include: notification to IMT (Incident Management Team) members and departmental heads, increased situation monitoring, review of plans at departmental level in preparation for a potential event,” the plan reads.

Austin Pugh, a training officer at the division of emergency management who also works with the college, said that it’s “the master plan that's going to be used for all types of emergencies.”

The plan created by the team serves all manner of emergencies, including wildfires. However, there is no specific plan for wildfire mitigation at the college.

“We have to be nimble enough because we don't know exactly how any crisis is going to unfold,” Hammes said. “Whether it’s a wildfire or whether it’s a flooding incident or whether it's a train wreck that happens that has hazardous material.”

Pugh said he hoped the campus community would be encouraged to know “wildfire is certainly not an afterthought” for the college.

On Feb. 25, 2025, during the Emergency Management team’s monthly workshop, they were looking over case studies of previous wildfires and previous incidents that have gone on throughout the country, Pugh said.

He noted that the college is not on the front lines of wildfire response, and its role is to prepare, support, and recover from incidents.

He also said that future campus improvements will follow the city’s fire codes.

“Whenever we do renovations, improvements, new buildings, all those kind of things, we do everything we can to make them what we call in the fire department, [...] class A,” he said.

Class A materials do not burn well and include materials such as gypsum, brick, and cement. The campus landscape is also well irrigated and, thus, “not very conductive,” Hammes said.

Hammes said that not all, but a lot of buildings on the CC campus have noncombustible exteriors. A few buildings on campus are made of wood, and Hammes said he would “love to future-proof a lot of these buildings.”

An ember needs fuel to burn. Buildings made of concrete are less likely, if at all, to catch on fire.

Outside of the college’s internal risk teams, the Pikes Peak Region Office of Emergency Management, or PPROEM, also plays a role in the safety of the campus.

“They provide emergency management, assistance, and resources,” said Pugh.

If a wildfire were to burn through campus, Hammes said the college has insurance policies in place to house students off campus.

Hammes said it is not a matter of “if” a wildfire is going to happen —“it's a matter of when it’s going to happen, right?”

You’re reading Burning Questions, a newsletter produced out of the Colorado College Journalism Institute with support from a National Science Foundation grant. Students produced some editions in their class “Reporting on Wildfires” in the fall of 2023 and the spring of 2025. Learn more about this newsletter here. 📬 Enter your email address to subscribe and get Burning Questions delivered to your inbox each time it comes out. You can reach us with questions, feedback, or tips by emailing burningquestionscc@gmail.com.