Fire as a Common Language: Bridging new wildfire science and public understanding

Plus, why is Colorado the only state without a state 'fire marshal,' Firehawk economics, and more

By: Ceyna Dawson and Grace Ellsworth

“Scientists talk too much,” said Jacob VanderRoest, a Ph.D. candidate at Colorado State University in Fort Collins who studies soil chemistry. “We can come across as really arrogant because we think we know a lot.”

With increasing wildfires worldwide, science is a field in which people are looking for answers. However, broad accessibility among the public can be difficult in journal articles like VanderRoest’s “Fire Impacts on the Soil Metabolome and Organic Matter Biodegradability.”

“That paper was not written for a general audience,” VanderRoest said.

Conversations about regrowth after fire might become challenging when the general public often experience much of the devastation and life-altering effects wildfires have had.

Oliver Keeley, a junior at Colorado College studying applied mathematics, experienced this devastation firsthand in Colorado’s most destructive wildfire, which happened in Boulder in 2021 and is known as the Marshall Fire.

Keeley was skiing in Vail upon receiving a phone call that his neighborhood was burning down, he said. With his house torched, his family in a long-term rental, and experiencing displacement, Keeley relied on his community.

After the Marshall Fire he came home from school to a completely refurnished home in Boulder made possible by his friends and community members.

“One big aspect I believe strongly on the human level is the phoenix rising out of the ashes,” Keeley said. “It is an opportunity to be grateful and rebuild a fire-resistant house.”

“I've always been a proponent of anything we can do to prevent this pain for everyone,” Keeley added. He thinks an integral part of preventing wildfires is through communicating to non-scientists.

“I think scientists could do a much better job of listening and adjusting how we talk about our research so it's easy for the public to understand,” Jacob VanderRoest said.

One way researchers are beginning to bridge that gap is through hands-on collaboration with communities.

Chris Guiterman, a paleo fire ecologist, hopes his work will help the public understand that fire isn't always destructive. It can also be beneficial.

Guiterman utilizes tree ring samples to determine the frequency, severity, and seasonality of fires to generate data on historical trends. While the science can seem abstract, Guiterman said he finds it rewarding to relay this information back to students and use research to impact communities.

“You do not need to use English,” Guiterman said, explaining how tree ring samples can speak for themselves. Science can become a mechanism to relay the common language of wildfires, he said.

Fire is a language scientists and the public have in common.

For Guiterman, a moment he knew he wanted to study fire was when he was driving in Tucson, Arizona. He observed the eerie nature of the smoke and how catastrophic wildfires could be.

“The whole landscape was floating away in the wind,” Guiterman said in a Zoom interview.

VanderRoest similarly experienced the gravity of wildfires in Fort Collins.

"It was the Alexander Mountain Fire. It was the first time I ever saw a wildfire in person. I could see the smoke plumes emanating from the foothills,” VanderRoest said over Zoom. “That was pretty terrifying.”

Fire is something that often is terrifying upon seeing it for the first time. It is these early experiences that drive scientists like Guiterman and VanderRoest to dig deeper into wildfire research.

This understanding of the catastrophic impacts wildfires can have is what fuels VanderRoest’s research into the chemistry of soil microbes after an intense burn.

When you think about wildfires, you probably picture raging flames consuming entire forests, leaving charred remnants behind.

But what you might not know is that beneath the ash, something much more intriguing is happening to the soil.

According to VanderRoest, wildfires might not be as bad for the environment as we initially thought, at least when it comes to soil.

VanderRoest’s research, which looks at how wildfires impact the soil’s chemistry and microbial life, has shown that, in some cases, fire can actually make soil tastier for bacteria.

Yes, you read that right.

It turns out, wildfires create a buffet for microbes living in the soil, which feast on proteins and sugars that are unlocked when the soil gets burned.

“Imagine you have an unburned marshmallow,” VanderRoest said. “It’s fine, but when you roast it over a fire, it gets a lot tastier.”

“That’s kind of what happens with the molecules in the soil,” he said. “Sometimes when these molecules are heated, the food, for lack of a better word, becomes tastier for the microbes.”

Who knew wildfires could be so delicious.

The marshmallow has undergone a transformation, a chemical reaction where heat changes its structure. In much the same way, the molecules in soil undergo similar changes when exposed to the intense heat of a wildfire.

For VanderRoest, this transformation is the key to understanding the impact of fire on the soil.

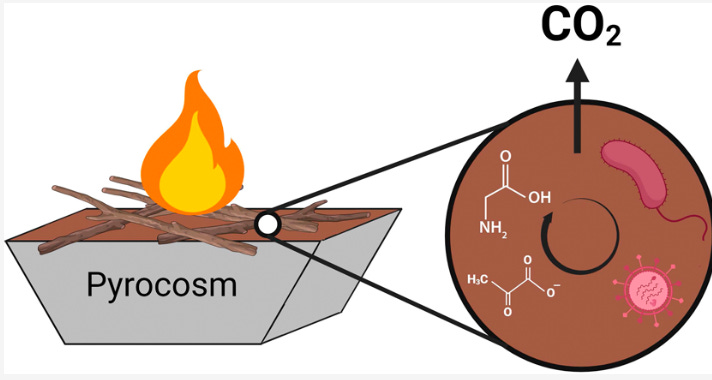

VanderRoest set up pyrocosms, miniature wildfire simulations made of steel. They looked at how fires impact something crucial for life on Earth: soil organic matter (SOM).

Soil organic matter is like the pantry of the soil, providing nutrients that help plants grow and feed the microbes that support life in the dirt. After a fire, though, things get tricky. While some parts of the SOM are tough and stick around, others might break down faster, and scientists wanted to know which parts of SOM are most affected.

They found that, after the fire, certain microbes, like Actinobacteria, Firmicutes, and Proteobacteria, flourished in the burned soil. They also discovered that the fire left behind more nitrogen in the soil and changed the chemistry of the soil, making it easier for some microbes to thrive.

“This research is not necessarily going to influence land management practices, but it helps us understand what to expect from these larger, more intense wildfires that are propagating because of climate change,” VanderRoest said.

VanderRoest hopes that with time his research into fire resilient microbes in soil will prompt other scientists to trace his findings in actual wildfires.

While science can be confusing and difficult to relay to the public, it is the passion for better understanding wildfires that can drive communication on new research.

Both VanderRoest and Guiterman find the most rewarding aspect of research on wildfires is to relay this information to not only the community, but to help others with increasing wildfires.

Guiterman has been working with the Navajo Forestry Department since 2013. He worked hand-in-hand with the department to break down what aspects of climate threaten the Navajo forests, he said.

“We worked together in the field. They shared data sets and helped me to make new ones,” Guiterman said.

VanderRoest continues to adapt his research and find digestible information he can relay to varying audiences. For example, presenting his new study with third and fifth graders to see how much they understand wildfires, and adjusting complex research meant for the graduate level to elementary students.

Researchers like VanderRoest and Guiterman are not just studying the flames, they're helping communities interpret the story fire tells. Whether it’s through decoding tree rings or making soil chemistry understandable to fifth graders, these scientists are building a bridge between the lab and the land.

In a world increasingly impacted by fire, understanding that shared language can be a powerful tool for resilience.

Colorado is the only state without a ‘Fire Marshal.’ Does it matter?

By: Samuel Carr and Julian Renschler

Last year, Hawaii’s Democratic governor, Josh Green, signed a law establishing a State Fire Marshal.

The move left Colorado as the only U.S. state not to employ such a position — at least in name.

Asked about why Colorado doesn’t have a state fire marshal during a recent meeting with Colorado College students in his office at the Capitol, Colorado Democratic Gov. Jared Polis said, “We have a fire chief . . . what would a fire marshal do that our fire chief doesn’t do?”

Colorado’s Division of Fire Prevention and Control, led by Mike Morgan, most closely resembles the authority of a state fire marshal.

According to the division’s website, the division’s main responsibilities range from “training firefighters to technological advancements in public safety, suppressing wildfires to building code enforcement.”

While a state fire marshal’s role varies from state to state, the National Association of State Marshals defines a fire marshal’s responsibilities as:

“fire safety code adoption and enforcement, fire and arson investigation, fire incident data reporting and analysis, public education and advising Governors and State Legislatures on fire protection.”

A close look at each of these definitions illuminates differences in the positions.

Perhaps the most significant of these is the lack of emphasis on fire and arson investigation in the mission statement provided by the CDFPC. A 2021 Colorado Public Radio article by Ben Markus and Veronica Penney found that only 43% of Colorado’s wildfires are assigned an exact initiation cause.

“Colorado is the only state in the U.S. without a state fire marshal,” the pair reported. “That means Colorado has less centralized control over fire investigations.”

Alternatively, states like Utah and Montana, which have a state fire marshal, name the ignition sources for more than 70% of human-caused fires, CPR News reported.

Chris Brunette, Section Fire Chief at the CDFPC in the Fire and Life Safety Section, views the lack of fire investigation as a problem.

“For 18 to 20 years, Colorado only had one fire investigator with one arson detector K-9,” he told Burning Questions.

Brunette said a new law “established that there was a need for additional resources for investigation in Colorado” and lawmakers gave the agency nine additional resources.

“So our team went from one investigator and one dog, now we have nine investigators and two accelerant detection K-9s,” he said.

While Brunette acknowledged that a statewide authority would be beneficial, the CDFPC serves many roles that a state fire marshal would.

“If you take a look at what we’re doing at the division of fire prevention and control, we're doing a lot of those functions as is,” he said.

Brad White, Fire Chief of Grand Fire in Grand County and president of the Colorado State Fire Chief’s Board, said there are reasons Colorado doesn’t have a state fire marshal.

“Between our plains and mountains and big cities and small cities, I think that things have kind of evolved and local municipalities and counties have taken it on themselves to adopt code and enforce code,” he told Burning Questions.

Colorado’s varying landscape and size make centralized control challenging, forcing districts to act internally.

“Colorado is very much a local-control state,” White said. “There are a lot of fire chiefs, too, who don’t think we need a state fire marshal.”

While some might be comfortable with minimal state code enforcement, White understands there could be benefits to establishing a state fire marshal.

“The state is not willing to adopt a statewide building code and statewide fire code and have a fire marshal oversee that, but they are willing to take pieces out of that and mandate local jurisdictions to enforce code,” he said. “A statewide fire marshal could really help on some of that.”

He added, however, that there are plenty of states where a state fire marshal doesn’t have a lot of control over much. Despite the lack of overarching state authority, White still finds the state as a useful resource.

“Even though the state doesn’t have a fire marshal they do have a Fire and Life Safety Division,” he said, “which is a huge resource for us.”

Fighting Fire with $24 Million: Is the Firehawk Colorado’s Best Defense?

By: Dessa Monat and Kai Fogelquist

In 2021, Colorado Democratic Gov. Jared Polis, who is finishing up his second term, signed a law authorizing the purchase of a $24 million S-70i Firehawk helicopter to fight wildfires in Colorado.

According to Fox31, after three years, the Firehawk took its first assignment on July 30th, 2024, during the Alexander Mountain Fire.

Speaking to the Colorado Sun, Mike Morgan, the director of Colorado’s Division of Fire Prevention and Control, explained that the helicopter was not built when it arrived in 2021, and after being outfitted for wildfires, there was an engine recall.

The S-70i is far from your average helicopter; it is specifically designed for fire, capable of transporting 11 firefighters and carrying more than 1,000 gallons of water.

On Wednesday, April 2, Polis spoke for roughly half an hour in his office about Colorado’s ongoing wildfire crisis with a class of Colorado College students who are taking “Reporting on Wildfires.”

Prior to the purchase of the helicopter, Polis said that Colorado often had to rely on out-of-state aircraft to fight in-state fires.

The state purchased its own state aircraft, Polis said, because “we weren’t always sure we could get what we needed when we needed it.”

Polis said when it came to the Firehawk, the “costs are minimal” and that the expense was primarily for the purchasing cost of the helicopter.

The governor’s office said in a follow-up email that the helicopter’s maintenance and operating costs currently total $2.5 million each year, plus an additional $7,500 for every hour the helicopter is in the air.

Last spring, KUSA 9News in Denver reported that “for more than a year now, Colorado taxpayers have paid for a pilot and mechanic to come to the state and fly a helicopter that isn’t actually allowed to fly yet.”

Then, last June, the Firehawk made headlines not because it fought a fire in Lake County, but because it wasn’t deployed. The converted Black Hawk helicopter wasn’t the closest asset to the fire and its pilots were still in training.

“It’s not a vehicle you go pick off the showroom floor,” Morgan told the 9NEWS TV station in Denver at the time. “These are very specific assets with very detailed specifications.”

According to Michael Kodas, a Pulitzer Prize-winning photojournalist, reporter, and author of the 2017 book “Megafire,” aircraft is most effective when it arrives early, performing initial retardant drops on smaller flames to help slow the spread and providing an aerial perspective that is crucial for coordinating firefighting efforts on the ground.

Joe Ortega, an engine boss for Stone Mountain Fire in Lake George, echoed the sentiment. “They are the ones who can see the whole fire from above, not the ground,” he said.

Still, some have argued that the dramatic image of aircraft in action can be somewhat misleading.

“People like to see [aerial suppression] because they want to see war declared on the fire threatening their property, but those resources are rarely making as much of a difference as they would like and are, again, very expensive,” Kodas said.

There are additional costs beyond monetary concerns in aerial operations.

According to data from the Wildland Fire Lessons Learned Center, which was established in 2002 with a mission to promote learning in the wildland fire service, out of 16 aviation fatalities in wildland fire since 2021, 10 involved helicopters.

“A firefighter’s risk of dying in a wildfire goes up tenfold the moment he or she steps into an aircraft, according to Andy Stahl, executive director at Forest Service Employees for Environmental Ethics,” Kodas wrote in “Megafire.”

As climate change causes the planet to get hotter and drier, a new type of wildfire is emerging, known as megafires. The U.S Forest Service defines a megafire as a fire that burns more than 100,000 acres of land. For context, this is equal to around 75,625 football fields (including end zones).

Megafires are exceptions to all of the rules of firefighting that we have come to know. With crown fires that can move flames from tree to tree in seconds, megafires can move up to 14.27 miles per hour, leaving firefighters running from fire, rather than fighting it.

According to an article by Ed Struzik in Yale Environment 360, a publication from the Yale School of the Environment, wind is one of the primary drivers that can turn an ordinary wildfire into a fast-moving, uncontrollable megafire. High winds not only fan the flames but also significantly hinder firefighting efforts from the air.

“The most explosive wildfires are wind driven, so when a fire is most dramatic, and the public is demanding to see aerial firefighting resources in the air, is when those resources are least effective and most dangerous to the personnel that are flying them,” Kodas said in an email.

Ultimately, climate change has been a key factor in increasing both the risk and intensity of wildfires.

According to Kodas, as fires become larger and more aggressive, aerial firefighting resources are becoming less effective, overwhelmed by the scale and speed of the blazes now seen across the United States.

In Kodas’s book, he cites a lack of government reports on the effectiveness of retardant drops.

Government databases from the Forest Service, BLM, and DOI, contain no current conclusive data on the effectiveness of retardant drops. The Forest Service collected data during March 2020, producing the Aerial Firefighting Use and Effectiveness (AFUE) report, which recommended, “[expanding] efforts to collect information on aircraft performance and effectiveness.”

Polis said that the state’s aircraft fleet, which includes more than just the Firehawk, has so far been “great” because of its effectiveness.

There are fires that we might not have heard about — or only heard about after they were extinguished — he said, that “might have become major fires had we not struck early.”

You’re reading Burning Questions, a newsletter produced out of the Colorado College Journalism Institute with support from a National Science Foundation grant. Students produced some editions in their class “Reporting on Wildfires” in the fall of 2023 and the spring of 2025. Learn more about this newsletter here. 📬 Enter your email address to subscribe and get Burning Questions delivered to your inbox each time it comes out. You can reach us with questions, feedback, or tips by emailing burningquestionscc@gmail.com.